Are Endometriosis, Adenomyosis, and PCOS Autoimmune Conditions?

By Our Daughters Foundation

More and more women are asking an important question: Could my hormone-related illness also be connected to my immune system?

Conditions like endometriosis, adenomyosis, and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) are often discussed in the context of reproductive health or hormonal imbalance. But researchers are beginning to explore deeper connections—specifically, whether autoimmunity plays a role in these diseases.

Let’s break down what the science says—and what questions remain unanswered.

Are Endometriosis, Adenomyosis, and PCOS Autoimmune Conditions?

By Our Daughters Foundation

More and more women are asking an important question: Could my hormone-related illness also be connected to my immune system?

Conditions like endometriosis, adenomyosis, and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) are often discussed in the context of reproductive health or hormonal imbalance. But researchers are beginning to explore deeper connections—specifically, whether autoimmunity plays a role in these diseases.

Let’s break down what the science says—and what questions remain unanswered.

What Is Autoimmunity?

The immune system is designed to protect the body from threats like viruses and bacteria. But in autoimmune diseases, the immune system becomes misguided and starts attacking the body’s own cells and tissues.

Common autoimmune conditions include:

• Lupus

• Rheumatoid arthritis

• Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

• Multiple sclerosis

Symptoms vary widely, but many autoimmune conditions involve chronic inflammation, pain, fatigue, and a pattern of flare-ups.

The Immune System and Endometriosis

Endometriosis occurs when tissue similar to the uterine lining grows outside the uterus—causing pain, inflammation, and sometimes infertility. While its exact cause is still debated, many researchers believe that the immune system fails to clear out these rogue cells effectively.

Several studies have found:

• Women with endometriosis often have higher levels of inflammatory markers, like cytokines and prostaglandins.

• Natural killer (NK) cell activity is lower in women with endometriosis, impairing the immune system’s ability to destroy misplaced cells.

• There are elevated autoantibodies in some patients, suggesting an autoimmune component.

Some scientists now consider endometriosis to be a non-classical autoimmune disease—showing many features of one without meeting all diagnostic criteria.

Further reading:

• NIH - Immune dysfunction in endometriosis: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30664929/

• Cleveland Clinic - Endometriosis and the Immune System: https://health.clevelandclinic.org/endometriosis-and-the-immune-system/

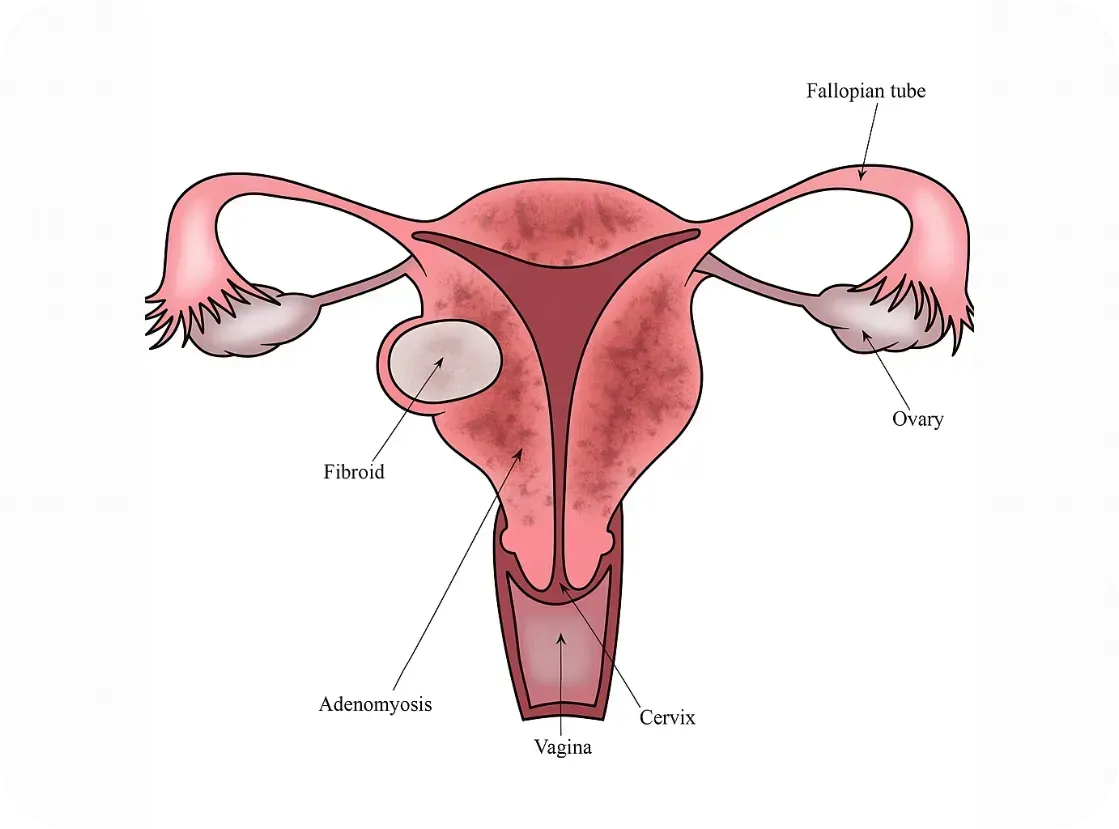

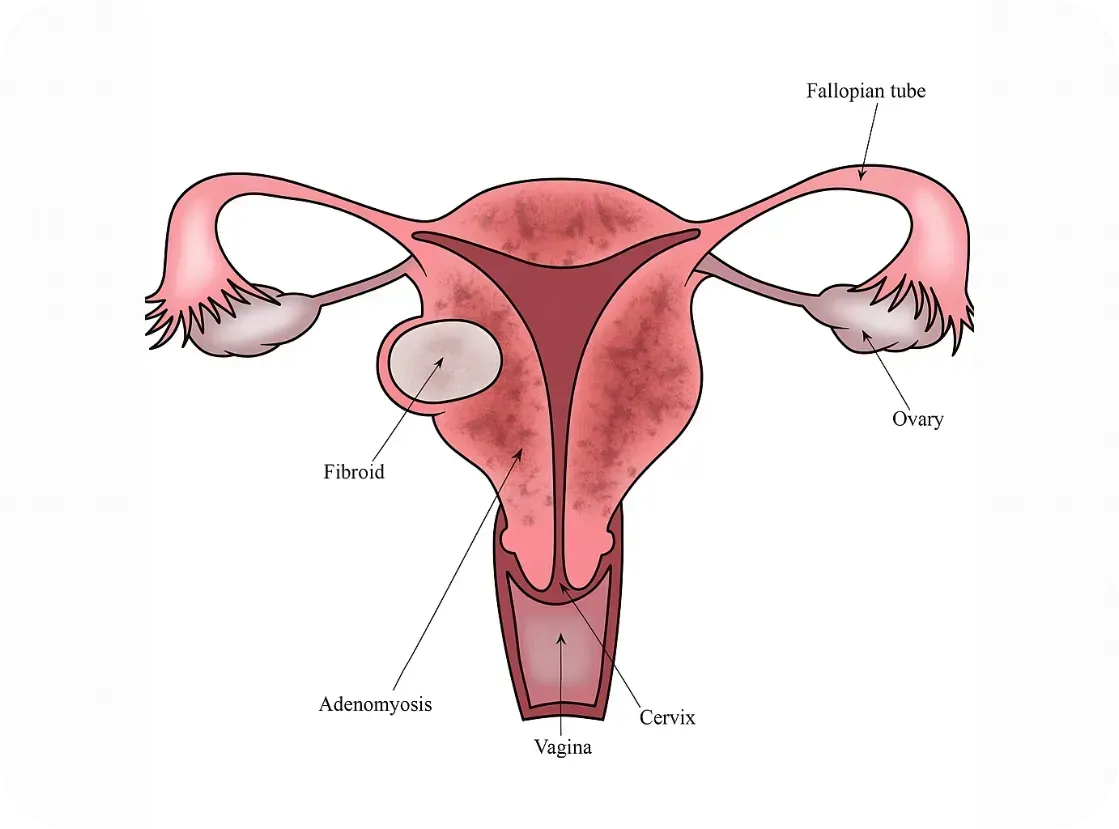

What About Adenomyosis?

Adenomyosis is sometimes called the "sister disease" of endometriosis. It occurs when endometrial tissue grows into the muscular wall of the uterus. It's less studied, but immune abnormalities have also been observed.

Research is still emerging, but here’s what we know:

• Women with adenomyosis show immune cell changes and chronic inflammation within the uterus.

• Some studies report increased macrophage and mast cell activity—cells involved in both immune defense and inflammation

• The condition often coexists with endometriosis, raising questions about shared immune pathways.

While it’s too early to label adenomyosis an autoimmune disorder, it may involve an immune imbalance that contributes to symptoms.

Further reading:

• Frontiers in Immunology - Immunopathogenesis of Adenomyosis: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.796273/full

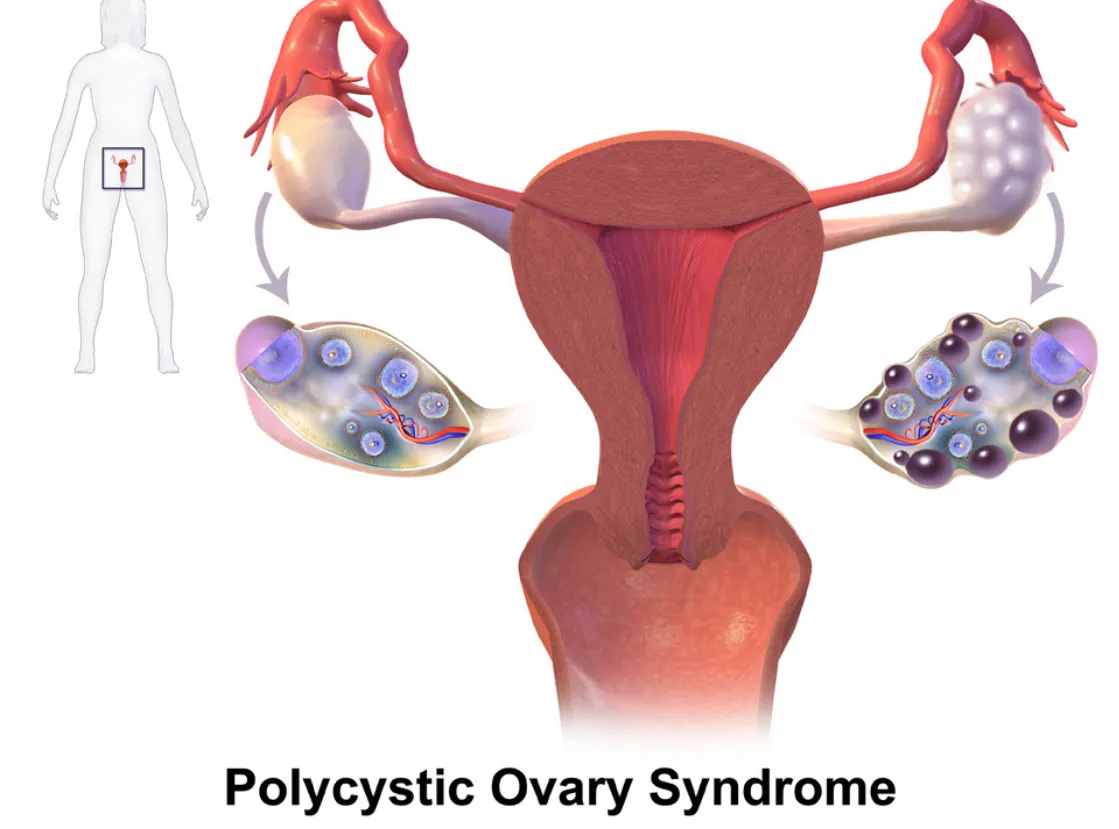

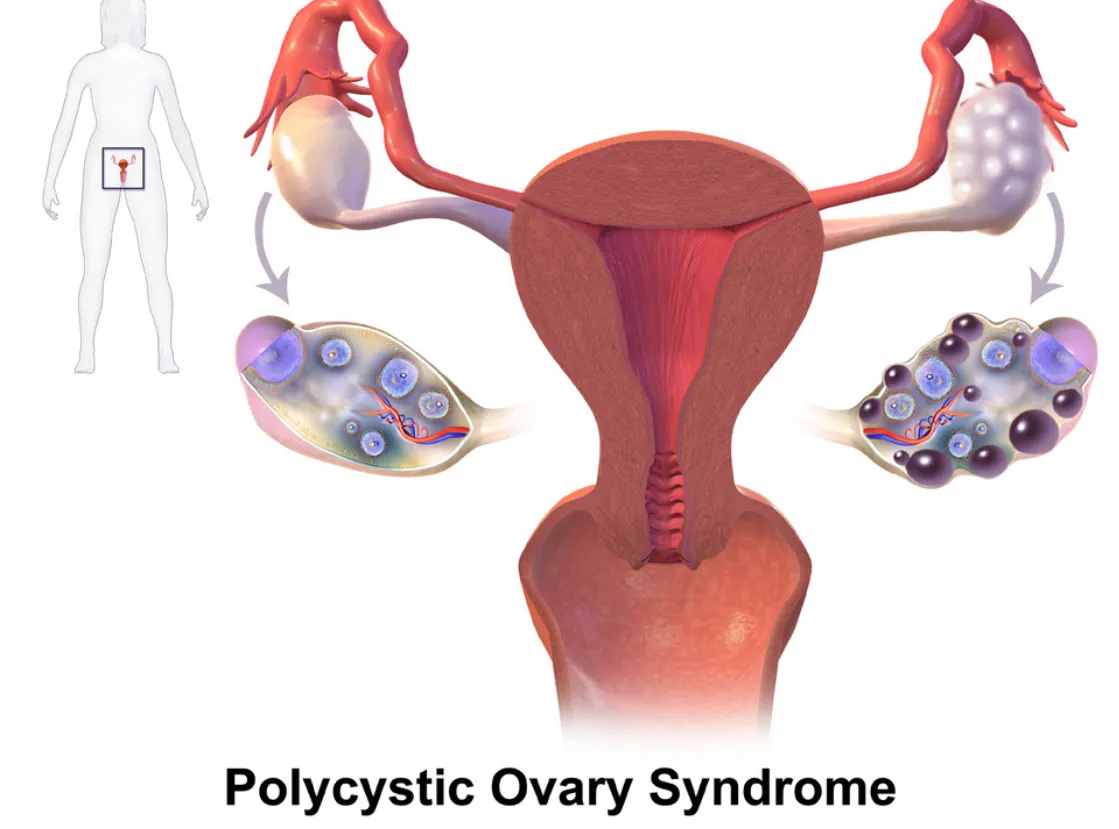

PCOS and Autoimmune Overlap

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is primarily known as a hormonal disorder involving androgen excess and insulin resistance. However, there’s growing interest in its immune connections, especially in women with chronic inflammation or thyroid issues.

Emerging links include:

• Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (an autoimmune thyroid disorder) is more common in women with PCOS.

• Inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) are often elevated in PCOS patients.

• Some PCOS patients have anti-ovarian antibodies, suggesting potential autoimmunity.

Still, the autoimmune theory is more speculative in PCOS than in endometriosis.

Further reading:

Further reading:

• Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism - PCOS and Autoimmune Disease: https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/106/9/e3536/6280755

Why Does This Matter?

If immune dysfunction is part of the puzzle, treatment strategies may need to shift. Many women with endometriosis, adenomyosis, or PCOS are treated solely with hormone suppression—but if autoimmunity is involved, we may also need to address inflammation, gut health, and immune regulation.

There’s also hope that newer treatments—like immunomodulatory therapies or even personalized nutrition and lifestyle interventions—could improve outcomes when tailored to the immune system’s role.

Bottom Line

We don’t yet have all the answers, but the research is evolving. Endometriosis, adenomyosis, and PCOS may not be traditional autoimmune diseases—but they often coexist with immune dysfunction, and the overlap deserves attention. At Our Daughters Foundation, we believe in honoring women’s voices, advocating for deeper research, and pursuing whole-body solutions.

If you’ve experienced overlapping conditions like endo, thyroid disease, or unexplained inflammation—you’re not alone.

What Is Autoimmunity?

The immune system is designed to protect the body from threats like viruses and bacteria. But in autoimmune diseases, the immune system becomes misguided and starts attacking the body’s own cells and tissues.

Common autoimmune conditions include:

• Lupus

• Rheumatoid arthritis

• Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

• Multiple sclerosis

Symptoms vary widely, but many autoimmune conditions involve chronic inflammation, pain, fatigue, and a pattern of flare-ups.

The Immune System and Endometriosis

Endometriosis occurs when tissue similar to the uterine lining grows outside the uterus—causing pain, inflammation, and sometimes infertility. While its exact cause is still debated, many researchers believe that the immune system fails to clear out these rogue cells effectively.

Several studies have found:

• Women with endometriosis often have higher levels of inflammatory markers, like cytokines and prostaglandins.

• Natural killer (NK) cell activity is lower in women with endometriosis, impairing the immune system’s ability to destroy misplaced cells.

• There are elevated autoantibodies in some patients, suggesting an autoimmune component.

Some scientists now consider endometriosis to be a non-classical autoimmune disease—showing many features of one without meeting all diagnostic criteria.

Further reading:

• NIH - Immune dysfunction in endometriosis: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30664929/

• Cleveland Clinic - Endometriosis and the Immune System: https://health.clevelandclinic.org/endometriosis-and-the-immune-system/

What About Adenomyosis?

Adenomyosis is sometimes called the "sister disease" of endometriosis. It occurs when endometrial tissue grows into the muscular wall of the uterus. It's less studied, but immune abnormalities have also been observed.

Research is still emerging, but here’s what we know:

• Women with adenomyosis show immune cell changes and chronic inflammation within the uterus.

• Some studies report increased macrophage and mast cell activity—cells involved in both immune defense and inflammation

• The condition often coexists with endometriosis, raising questions about shared immune pathways.

While it’s too early to label adenomyosis an autoimmune disorder, it may involve an immune imbalance that contributes to symptoms.

Further reading:

• Frontiers in Immunology - Immunopathogenesis of Adenomyosis: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.796273/full

PCOS and Autoimmune Overlap

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is primarily known as a hormonal disorder involving androgen excess and insulin resistance. However, there’s growing interest in its immune connections, especially in women with chronic inflammation or thyroid issues.

Emerging links include:

• Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (an autoimmune thyroid disorder) is more common in women with PCOS.

• Inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) are often elevated in PCOS patients.

• Some PCOS patients have anti-ovarian antibodies, suggesting potential autoimmunity.

Still, the autoimmune theory is more speculative in PCOS than in endometriosis.

Further reading:

Further reading:

• Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism - PCOS and Autoimmune Disease: https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/106/9/e3536/6280755

Why Does This Matter?

If immune dysfunction is part of the puzzle, treatment strategies may need to shift. Many women with endometriosis, adenomyosis, or PCOS are treated solely with hormone suppression—but if autoimmunity is involved, we may also need to address inflammation, gut health, and immune regulation.

There’s also hope that newer treatments—like immunomodulatory therapies or even personalized nutrition and lifestyle interventions—could improve outcomes when tailored to the immune system’s role.

Bottom Line

We don’t yet have all the answers, but the research is evolving. Endometriosis, adenomyosis, and PCOS may not be traditional autoimmune diseases—but they often coexist with immune dysfunction, and the overlap deserves attention. At Our Daughters Foundation, we believe in honoring women’s voices, advocating for deeper research, and pursuing whole-body solutions.

If you’ve experienced overlapping conditions like endo, thyroid disease, or unexplained inflammation—you’re not alone.

Join Us: Make a Difference Today

Your support can transform lives. Every donation helps us fund research, advocate for better care, and provide essential grants to women facing debilitating conditions.

Join Us: Make a Difference Today

Your support can transform lives. Every donation helps us fund research, advocate for better care, and provide essential grants to women facing debilitating conditions.

Neuroangiogenesis: Nerves & Blood Vessels Fueling Endo

How Nerves and Blood Vessels Fuel Endometriosis: Understanding Neuroangiogenesis

When we think of endometriosis, we often imagine painful periods, reproductive complications, or fatigue. But beneath these symptoms lies a deeper, more complex process—one that helps explain why this condition is so painful, why it often gets worse over time, and why standard treatments don’t always work.

That process is called neuroangiogenesis—a mouthful of a word that simply means the simultaneous growth of new nerves (neuro-) and blood vessels (-angiogenesis). And it’s changing the way experts understand and treat endometriosis.

What Is Neuroangiogenesis?

Dr. Vimee Bindra, a leading gynecologist and endometriosis specialist, puts it plainly:

“Neuroangiogenesis fuels the pain of endometriosis.”

In her article, she explains that endometriotic lesions aren’t passive—they actively create their own support systems. These lesions grow tiny blood vessels that bring in oxygen and nutrients, helping them survive even in hostile environments like the pelvis, bowel, bladder, or abdominal wall. But even more troubling, they also stimulate nerve growth—making the affected areas more sensitive and painful.

This explains why pain in endometriosis isn’t limited to menstruation. For many women, it’s constant. It flares during ovulation. It radiates into the legs or back. It worsens with movement, digestion, or intimacy.

Why? Because it’s not just inflammation—it’s nerve-driven pain. The same biological mechanisms that help our body heal after injury are being hijacked by endometriosis lesions to sustain and spread the disease.

The Science Behind It

Research supports this dual growth model:

Studies have found that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which encourages new blood vessel formation, is overproduced in endometriotic tissue.

At the same time, nerve growth factor (NGF) is elevated, helping lesions become densely innervated and hypersensitive.

In fact, some studies report that lesions have 10 to 50 times more nerve fibers than similar tissue in people without endometriosis.

This combination of angiogenesis and neurogenesis makes endometriosis uniquely painful—and uniquely difficult to treat with one-size-fits-all approaches.

Why It Matters

Pain is not just a symptom of endometriosis—it’s a sign of progression.

Neuroangiogenesis helps explain why:

Endometriosis pain doesn’t always correlate with the size of lesions.

Pain can continue even after menopause or a hysterectomy.

Hormonal treatments alone often fail to fully relieve symptoms.

Dr. Bindra emphasizes that neuroangiogenesis helps us reframe endometriosis not just as a hormonal or reproductive issue, but as a neurovascular condition—one that affects the immune system, the nervous system, and the vascular system all at once.

Understanding this has the potential to unlock better, longer-lasting solutions.

A New Direction for Treatment

This evolving science is already inspiring a shift in how endometriosis is treated:

1. Anti-Angiogenic Therapies

By targeting VEGF and other blood vessel growth signals, researchers hope to “starve” lesions and stop them from spreading. Some cancer drugs are being investigated for this purpose, including bevacizumab, which blocks VEGF.

2. Nerve-Targeted Treatments

Medications that calm overactive nerves—such as gabapentin, pregabalin, or even newer biologics aimed at NGF—may help reduce pain at its neurological source.

3. Precision Surgery

Excision surgery done by skilled specialists—especially when guided by lesion-mapping tools like the ENZIAN classification—can remove deep, infiltrating lesions and decompress trapped nerves. This type of surgery is different from ablation and requires specialized expertise, but it can offer significant relief.

As Dr. Bindra notes in her clinical work, identifying the exact location and depth of lesions—especially those invading nerves—is critical for improving surgical outcomes.

Hope on the Horizon

At Our Daughters Foundation, we believe that informed care is empowered care. And understanding neuroangiogenesis gives us all a better framework for navigating endometriosis.

It helps patients explain their pain.

It helps doctors pursue more targeted treatments.

And it helps researchers continue moving toward real, long-term solutions.

You are not imagining your pain. You are not overreacting. You are not alone.

“The more we learn about how endometriosis builds its own nerve and blood supply, the closer we get to stopping it at the source.” – Dr. Vimee Bindra

References

Dr. Vimee Bindra

“Neuroangiogenesis: How Nerves and Blood Vessels Fuel Endometriosis”

https://www.drvimeebindra.com/neuroangiogenesis-how-nerves-and-blood-vessels-fuel-endometriosis/Dr. Vimee Bindra (LinkedIn)

Quote: “Neuroangiogenesis fuels the pain of endometriosis…”

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/dr-vimee-bindra-basu-7514765b_letstalkendo-endometriosisawarenessmonth-activity-7305270488694501381-KtCYTokushige N, Markham R, Russell P, Fraser IS

“Nerve fibers in peritoneal endometriosis”

Human Reproduction, 2006.

https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/del009Taylor RN, Yu J, Torres PB, Schickedanz AC, Park JK, Mueller MD

“Mechanistic and therapeutic implications of angiogenesis in endometriosis”

Reproductive Sciences, 2020.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1933719119899937Arnold J, Barcena de Arellano ML, Rüster C, et al.

“Immunologic alterations in endometriosis: current understanding and future therapeutic implications”

Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2020.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7349441/Ferrero S, Gillott DJ, Remorgida V, et al.

“Use of antiangiogenic agents to treat endometriosis: a review”

Gynecological Endocrinology, 2010.

https://doi.org/10.3109/09513590903247814Bindra V, et al.

“Clinical Characteristics and Locations of Lesions in Patients with Endometriosis Using ENZIAN Classification”

Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of India, 2025.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40390882/