Are Endometriosis, Adenomyosis, and PCOS Autoimmune Conditions?

By Our Daughters Foundation

More and more women are asking an important question: Could my hormone-related illness also be connected to my immune system?

Conditions like endometriosis, adenomyosis, and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) are often discussed in the context of reproductive health or hormonal imbalance. But researchers are beginning to explore deeper connections—specifically, whether autoimmunity plays a role in these diseases.

Let’s break down what the science says—and what questions remain unanswered.

Are Endometriosis, Adenomyosis, and PCOS Autoimmune Conditions?

By Our Daughters Foundation

More and more women are asking an important question: Could my hormone-related illness also be connected to my immune system?

Conditions like endometriosis, adenomyosis, and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) are often discussed in the context of reproductive health or hormonal imbalance. But researchers are beginning to explore deeper connections—specifically, whether autoimmunity plays a role in these diseases.

Let’s break down what the science says—and what questions remain unanswered.

What Is Autoimmunity?

The immune system is designed to protect the body from threats like viruses and bacteria. But in autoimmune diseases, the immune system becomes misguided and starts attacking the body’s own cells and tissues.

Common autoimmune conditions include:

• Lupus

• Rheumatoid arthritis

• Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

• Multiple sclerosis

Symptoms vary widely, but many autoimmune conditions involve chronic inflammation, pain, fatigue, and a pattern of flare-ups.

The Immune System and Endometriosis

Endometriosis occurs when tissue similar to the uterine lining grows outside the uterus—causing pain, inflammation, and sometimes infertility. While its exact cause is still debated, many researchers believe that the immune system fails to clear out these rogue cells effectively.

Several studies have found:

• Women with endometriosis often have higher levels of inflammatory markers, like cytokines and prostaglandins.

• Natural killer (NK) cell activity is lower in women with endometriosis, impairing the immune system’s ability to destroy misplaced cells.

• There are elevated autoantibodies in some patients, suggesting an autoimmune component.

Some scientists now consider endometriosis to be a non-classical autoimmune disease—showing many features of one without meeting all diagnostic criteria.

Further reading:

• NIH - Immune dysfunction in endometriosis: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30664929/

• Cleveland Clinic - Endometriosis and the Immune System: https://health.clevelandclinic.org/endometriosis-and-the-immune-system/

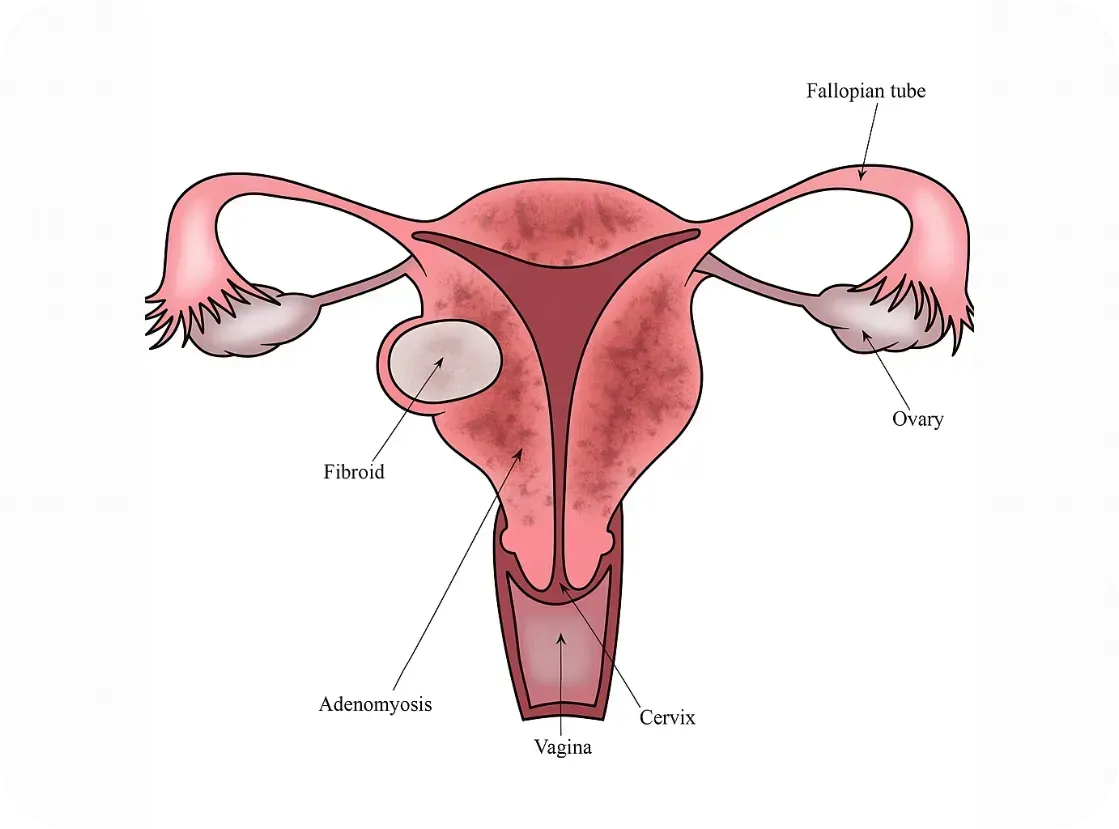

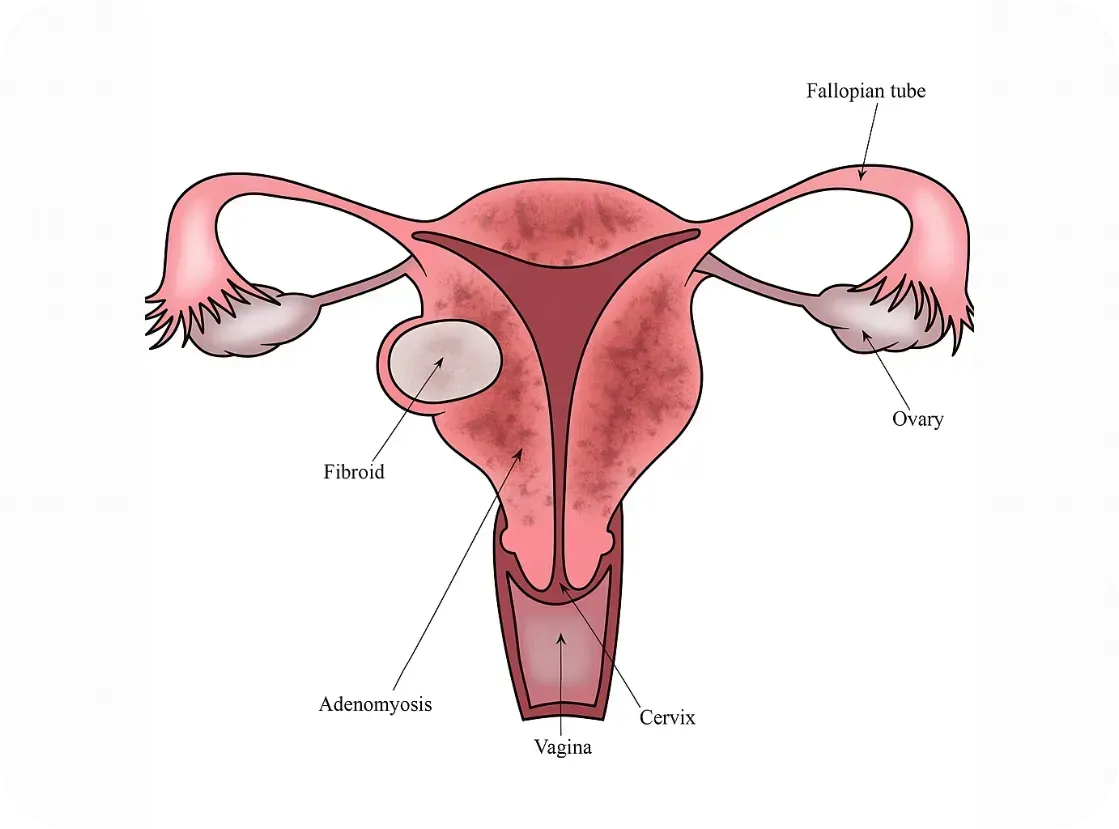

What About Adenomyosis?

Adenomyosis is sometimes called the "sister disease" of endometriosis. It occurs when endometrial tissue grows into the muscular wall of the uterus. It's less studied, but immune abnormalities have also been observed.

Research is still emerging, but here’s what we know:

• Women with adenomyosis show immune cell changes and chronic inflammation within the uterus.

• Some studies report increased macrophage and mast cell activity—cells involved in both immune defense and inflammation

• The condition often coexists with endometriosis, raising questions about shared immune pathways.

While it’s too early to label adenomyosis an autoimmune disorder, it may involve an immune imbalance that contributes to symptoms.

Further reading:

• Frontiers in Immunology - Immunopathogenesis of Adenomyosis: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.796273/full

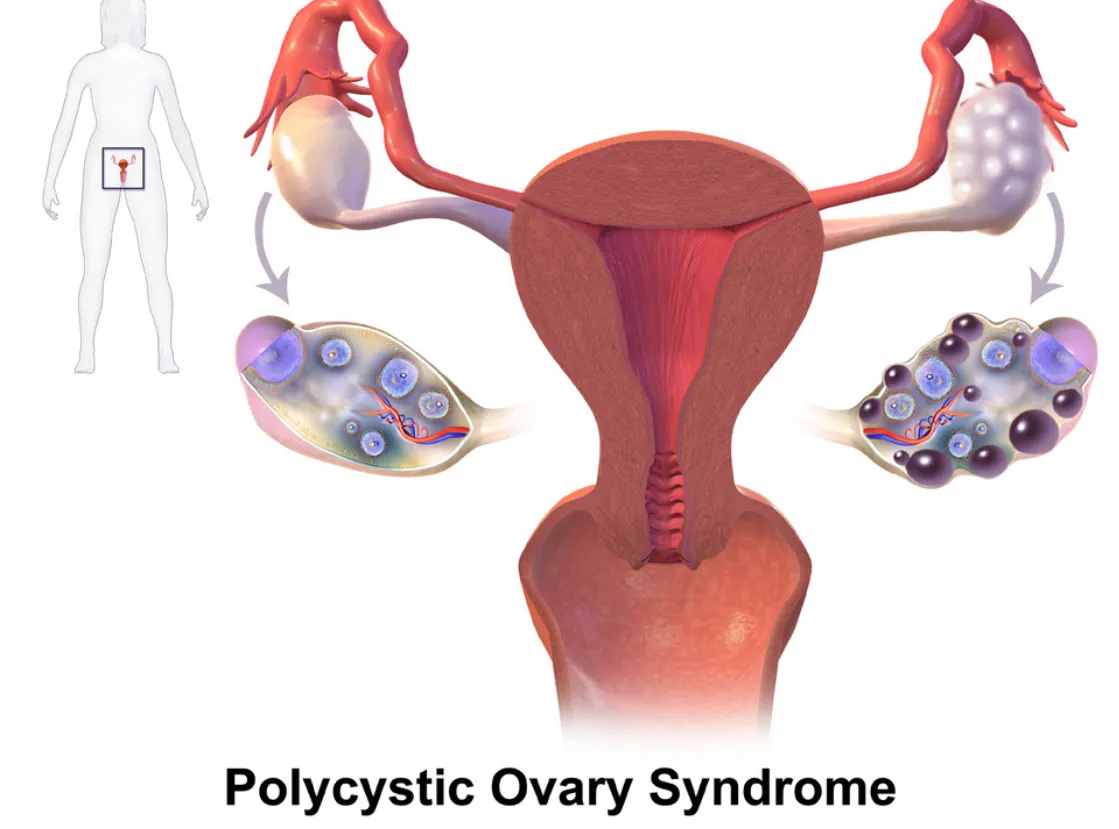

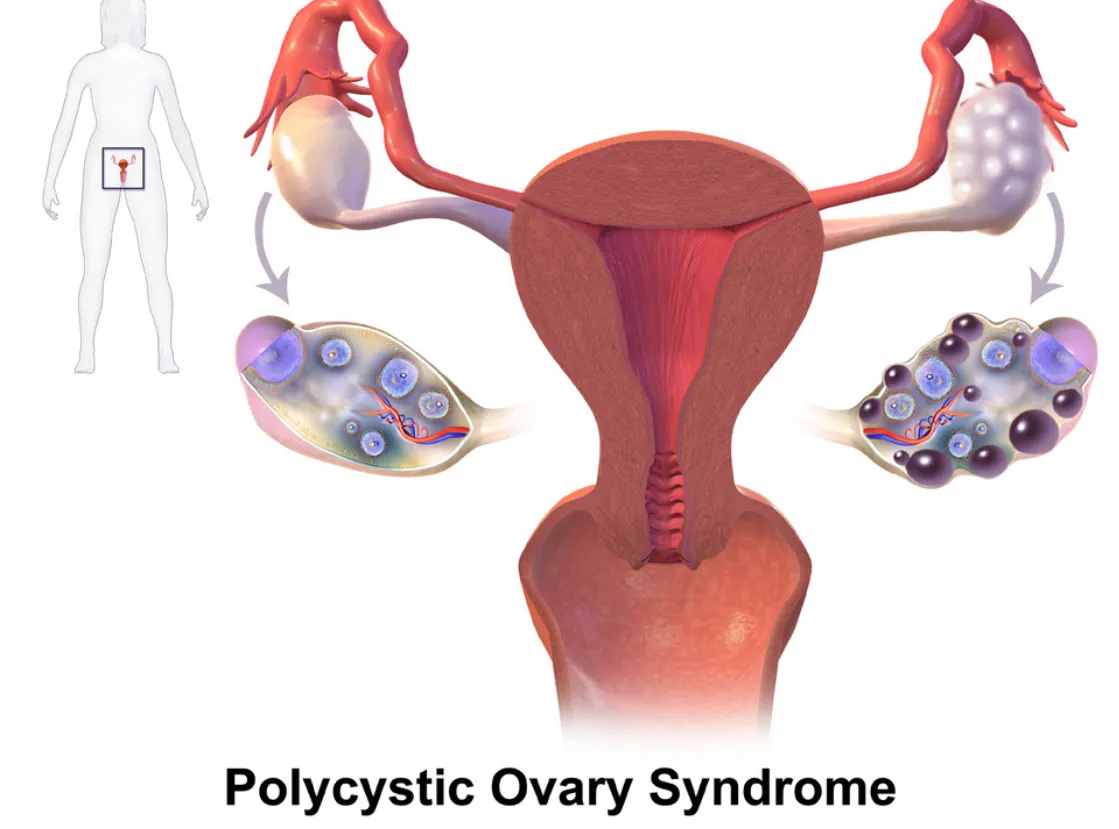

PCOS and Autoimmune Overlap

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is primarily known as a hormonal disorder involving androgen excess and insulin resistance. However, there’s growing interest in its immune connections, especially in women with chronic inflammation or thyroid issues.

Emerging links include:

• Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (an autoimmune thyroid disorder) is more common in women with PCOS.

• Inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) are often elevated in PCOS patients.

• Some PCOS patients have anti-ovarian antibodies, suggesting potential autoimmunity.

Still, the autoimmune theory is more speculative in PCOS than in endometriosis.

Further reading:

Further reading:

• Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism - PCOS and Autoimmune Disease: https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/106/9/e3536/6280755

Why Does This Matter?

If immune dysfunction is part of the puzzle, treatment strategies may need to shift. Many women with endometriosis, adenomyosis, or PCOS are treated solely with hormone suppression—but if autoimmunity is involved, we may also need to address inflammation, gut health, and immune regulation.

There’s also hope that newer treatments—like immunomodulatory therapies or even personalized nutrition and lifestyle interventions—could improve outcomes when tailored to the immune system’s role.

Bottom Line

We don’t yet have all the answers, but the research is evolving. Endometriosis, adenomyosis, and PCOS may not be traditional autoimmune diseases—but they often coexist with immune dysfunction, and the overlap deserves attention. At Our Daughters Foundation, we believe in honoring women’s voices, advocating for deeper research, and pursuing whole-body solutions.

If you’ve experienced overlapping conditions like endo, thyroid disease, or unexplained inflammation—you’re not alone.

What Is Autoimmunity?

The immune system is designed to protect the body from threats like viruses and bacteria. But in autoimmune diseases, the immune system becomes misguided and starts attacking the body’s own cells and tissues.

Common autoimmune conditions include:

• Lupus

• Rheumatoid arthritis

• Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

• Multiple sclerosis

Symptoms vary widely, but many autoimmune conditions involve chronic inflammation, pain, fatigue, and a pattern of flare-ups.

The Immune System and Endometriosis

Endometriosis occurs when tissue similar to the uterine lining grows outside the uterus—causing pain, inflammation, and sometimes infertility. While its exact cause is still debated, many researchers believe that the immune system fails to clear out these rogue cells effectively.

Several studies have found:

• Women with endometriosis often have higher levels of inflammatory markers, like cytokines and prostaglandins.

• Natural killer (NK) cell activity is lower in women with endometriosis, impairing the immune system’s ability to destroy misplaced cells.

• There are elevated autoantibodies in some patients, suggesting an autoimmune component.

Some scientists now consider endometriosis to be a non-classical autoimmune disease—showing many features of one without meeting all diagnostic criteria.

Further reading:

• NIH - Immune dysfunction in endometriosis: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30664929/

• Cleveland Clinic - Endometriosis and the Immune System: https://health.clevelandclinic.org/endometriosis-and-the-immune-system/

What About Adenomyosis?

Adenomyosis is sometimes called the "sister disease" of endometriosis. It occurs when endometrial tissue grows into the muscular wall of the uterus. It's less studied, but immune abnormalities have also been observed.

Research is still emerging, but here’s what we know:

• Women with adenomyosis show immune cell changes and chronic inflammation within the uterus.

• Some studies report increased macrophage and mast cell activity—cells involved in both immune defense and inflammation

• The condition often coexists with endometriosis, raising questions about shared immune pathways.

While it’s too early to label adenomyosis an autoimmune disorder, it may involve an immune imbalance that contributes to symptoms.

Further reading:

• Frontiers in Immunology - Immunopathogenesis of Adenomyosis: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.796273/full

PCOS and Autoimmune Overlap

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is primarily known as a hormonal disorder involving androgen excess and insulin resistance. However, there’s growing interest in its immune connections, especially in women with chronic inflammation or thyroid issues.

Emerging links include:

• Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (an autoimmune thyroid disorder) is more common in women with PCOS.

• Inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) are often elevated in PCOS patients.

• Some PCOS patients have anti-ovarian antibodies, suggesting potential autoimmunity.

Still, the autoimmune theory is more speculative in PCOS than in endometriosis.

Further reading:

Further reading:

• Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism - PCOS and Autoimmune Disease: https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/106/9/e3536/6280755

Why Does This Matter?

If immune dysfunction is part of the puzzle, treatment strategies may need to shift. Many women with endometriosis, adenomyosis, or PCOS are treated solely with hormone suppression—but if autoimmunity is involved, we may also need to address inflammation, gut health, and immune regulation.

There’s also hope that newer treatments—like immunomodulatory therapies or even personalized nutrition and lifestyle interventions—could improve outcomes when tailored to the immune system’s role.

Bottom Line

We don’t yet have all the answers, but the research is evolving. Endometriosis, adenomyosis, and PCOS may not be traditional autoimmune diseases—but they often coexist with immune dysfunction, and the overlap deserves attention. At Our Daughters Foundation, we believe in honoring women’s voices, advocating for deeper research, and pursuing whole-body solutions.

If you’ve experienced overlapping conditions like endo, thyroid disease, or unexplained inflammation—you’re not alone.

Join Us: Make a Difference Today

Your support can transform lives. Every donation helps us fund research, advocate for better care, and provide essential grants to women facing debilitating conditions.

Join Us: Make a Difference Today

Your support can transform lives. Every donation helps us fund research, advocate for better care, and provide essential grants to women facing debilitating conditions.

Why Menopause Does Not Treat Endometriosis

Why menopause does not treat endometriosis

Quite often endometriosis patients are told to have their ovaries removed or put their activity on hold with hormonal medication as a way of treating the disease. As demonstrated by some studies, endometriosis lesions have the potential to produce their own oestrogen, as such removal of ovaries or temporary menopause will have little or no impact on the endometriosis itself.

What is oestrogen?

Various laboratory studies have shown that endometriosis is an oestrogen dependent disease. In females, the highest quantity of oestrogens is produced in ovaries. It is also produced in small amounts in other organs such as liver, heart and brain. The oestrogen is divided in three categories: E1 known as estrone, E2 known as estradiol and E3 known as estriol.

Out of all 3 oestrogen types the E2 is the most potent and it is active during the fertility period. E1 is more potent after the menopause and it is synthesised in adipose tissue from adrenal dehydroepiandrosterone, whilst E3 has a role in pregnancy, it’s produced by placenta during pregnancy, and it is the least potent one.

What is aromatase?

The conversion of androstenedione and testosterone E1 and E2 is done by the aromatase. Aromatase is expressed in places such as the brain, gonads, blood vessels, adipose tissue, liver, bone, skin, and endometrium. In fertile women the oestrogen biosynthesis takes place in the ovary, while in postmenopausal women it takes in extraglandular tissues such as adipose tissue and skin.

The role of aromatase expression in endometriosis

One of the first studies that have demonstrated the presence of aromatase expression in endometriosis implants was published in 1996.

To demonstrate the presence of aromatase in endometriosis implants, the scholars have conducted a study analysing and comparing biopsy samples from:

endometriosis implants from pelvic peritoneum (posterior cul-de-sac, bladder, and anterior cul-de-sac);

endometrial tissue in patients with histologically documented pelvic endometriosis;

pelvic peritoneal distal and normal endometrial tissues from women without endometriosis;

Based on the results, P450arom transcripts were detected in all endometriosis implants.The highest presence of P450arom was detected in endometriosis implants that involved the full thickness of the anterior abdominal wall. Also, in the core of the endometriosis implants, the P450arom transcript level was 4-fold higher than that in the surrounding adipose tissue. The authors concluded that the possibility of oestrogen production in endometriosis implants might promote their growth.

Other studies have also demonstrated a higher expression of aromatase in endometriosis implants. Zeitoun KM et al. concluded that molecular aberrations can impact the oestrogen biosynthesis leading to an increased local concentration of E2. The aberrant expressed aromatase in the endometriotic stromal cells converts C19, steroids to oestrogens.

Moreover, a immunohistochemical analysis found that the local estrogen production by aberrantly elevated aromatase takes place only in endometriosis and adenomyosis, and not in the normal endometrium.

In conclusion, removal of ovaries to stop the production of oestrogen as a way of treating endometriosis is not an efficient method, especially if endometriosis lesions are not removed. Endometriosis produces its own oestrogen and as long as the disease is left beyond it will continue to cause symptoms and impact organs.

-Athens Centre for Endometriosis