The Overlooked Link: Allen-Masters Syndrome and Endometriosis

How a Little-Known Condition Can Complicate Diagnosis and Treatment for Women in Pain

The Overlooked Link: Allen-Masters Syndrome and Endometriosis

How a Little-Known Condition Can Complicate Diagnosis and Treatment for Women in Pain

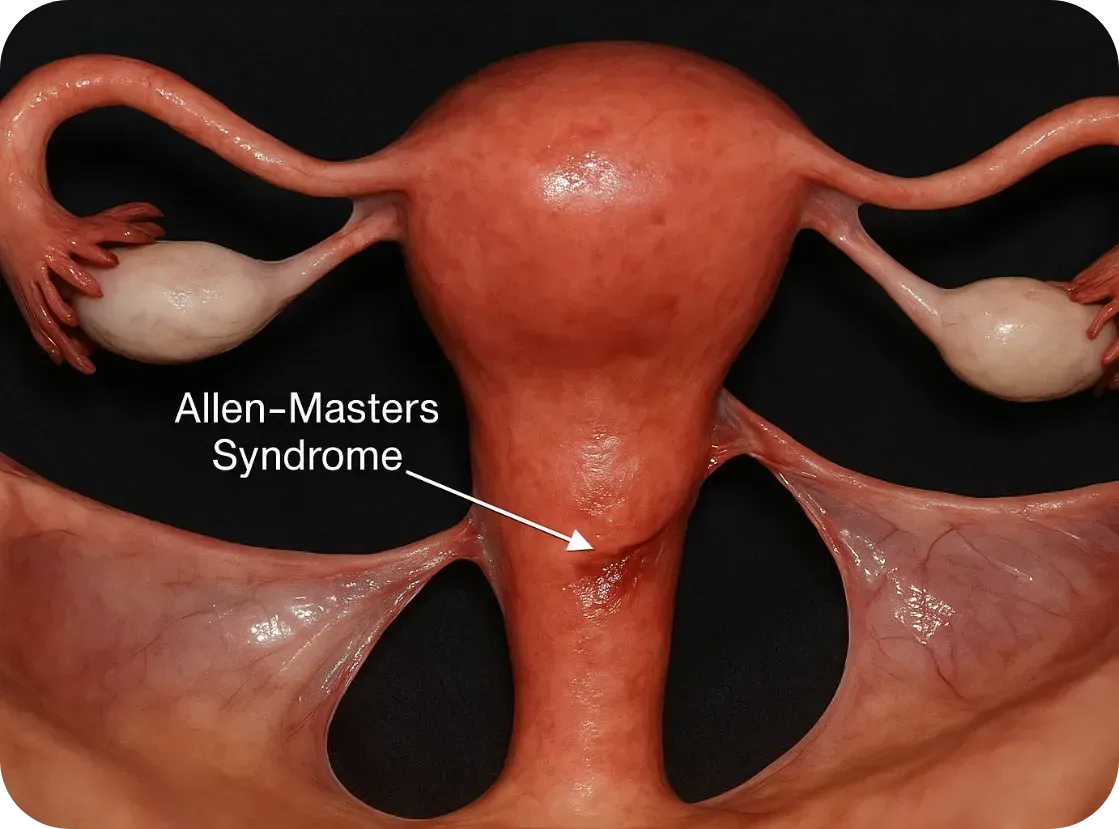

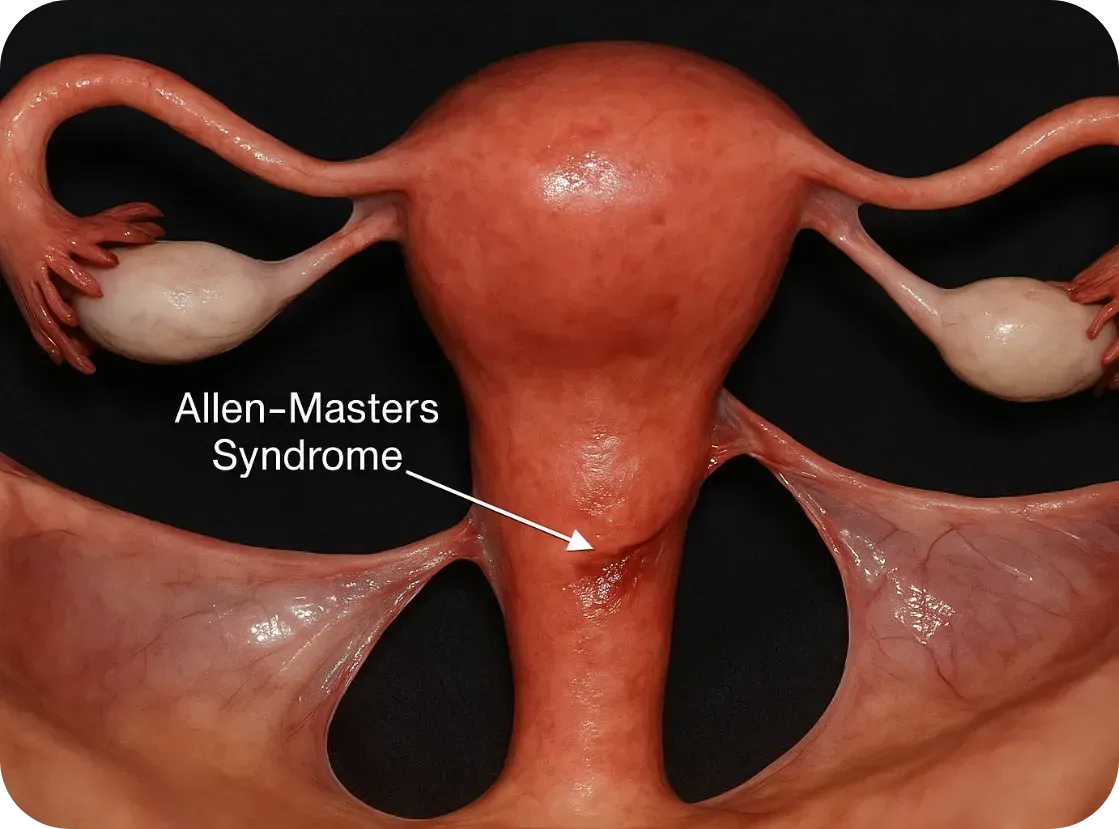

What Is Allen-Masters Syndrome?

Allen-Masters Syndrome (AMS) refers to a condition where the ligaments that support the uterus become torn or stretched, often due to trauma or childbirth. The damage causes the uterus to become hypermobile, or “floppy,” which can lead to chronic pelvic pain, abnormal uterine positioning, and a range of gynecological symptoms.

First described in the 1950s by gynecologists Allen and Masters, the syndrome was initially observed in women who experienced difficult or forceful deliveries. However, it's now known that other pelvic trauma—such as surgeries, repeated inflammation, or even invasive endometriosis—can also play a role.

How It Feels: The Symptoms

The symptoms of AMS often overlap with other pelvic disorders, including endometriosis, which makes it incredibly hard to diagnose:

• Chronic pelvic pain, especially on one side

• Pain during intercourse (dyspareunia)

• A feeling of “heaviness” or dragging in the pelvis

• Irregular bleeding or spotting

• Referred pain to the lower back or legs

• Pain made worse by certain movements or positions

These symptoms can persist even after surgery for endometriosis or fibroids, leaving women frustrated and wondering why their treatments didn’t work.

The Complication with Endometriosis

Endometriosis and Allen-Masters Syndrome can coexist—and when they do, they complicate each other.

Endometriosis and Allen-Masters Syndrome can coexist—and when they do, they complicate each other.

Here’s how:

1. Mimicking or Masking Each Other

AMS pain can feel nearly identical to endometriosis. In laparoscopic surgery, torn ligaments or peritoneal defects might be mistaken for endometriosis—or missed entirely.

2. Worsening Each Other

The uterine instability caused by AMS may increase friction and inflammation in the pelvis, potentially exacerbating endometriosis symptoms. Likewise, the invasive nature of endometriosis can weaken uterine ligaments, creating a cycle of worsening pain.

3. Delaying Diagnosis

Because AMS isn’t well known, many surgeons focus only on excising visible endometriosis lesions. If ligament tears or pelvic instability aren’t also addressed, pain may persist despite "successful" surgery.

4. Influencing Fertility

While endometriosis is a known contributor to infertility, AMS can add to the challenge by altering the position of the uterus, interfering with sperm transport, or making embryo implantation more difficult.

Diagnosis: Why It’s Often Missed

AMS is best diagnosed through clinical examination and often requires a high index of suspicion from an experienced gynecologic surgeon. Imaging like MRI or ultrasound may not show ligament damage clearly. In some cases, laparoscopic exploration is the only way to confirm it, by observing a hypermobile uterus or peritoneal defects (like dimples or windows in the pelvic lining).

Unfortunately, many OB/GYNs are not trained to look for Allen-Masters Syndrome, which means it’s often overlooked—especially in patients already diagnosed with endometriosis

What Can Be Done?

If AMS is suspected, the treatment may include:

• Pelvic physical therapy to support surrounding muscles and reduce pain

• Surgical repair or suspension of the damaged ligaments, often during laparoscopy

• Pain management strategies including nerve blocks or hormonal regulation if endometriosis is also present

• Lifestyle modifications to reduce strain on the pelvis (avoiding certain exercises, managing constipation, etc.)

The Takeaway

Allen-Masters Syndrome may not be as well-known as endometriosis, but its impact is very real—especially for women who feel like they've tried everything and still have no answers.

If you’ve had surgery for endometriosis and your pain persists, or if your symptoms don’t quite fit the typical endo profile, it might be worth asking your doctor about Allen-Masters Syndrome.

Women deserve full answers—not partial relief.

Sources & Further Reading

• Howard FM. (2003). Chronic Pelvic Pain. Obstetrics and Gynecology

• Vercellini P et al. (2006). Chronic pelvic pain: pathogenesis and therapy. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology

• Tu FF et al. (2017). Beyond Endometriosis: Recognizing and Treating Comorbid Pelvic Pain Disorders. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology

What Is Allen-Masters Syndrome?

Allen-Masters Syndrome (AMS) refers to a condition where the ligaments that support the uterus become torn or stretched, often due to trauma or childbirth. The damage causes the uterus to become hypermobile, or “floppy,” which can lead to chronic pelvic pain, abnormal uterine positioning, and a range of gynecological symptoms.

First described in the 1950s by gynecologists Allen and Masters, the syndrome was initially observed in women who experienced difficult or forceful deliveries. However, it's now known that other pelvic trauma—such as surgeries, repeated inflammation, or even invasive endometriosis—can also play a role.

How It Feels: The Symptoms

The symptoms of AMS often overlap with other pelvic disorders, including endometriosis, which makes it incredibly hard to diagnose:

• Chronic pelvic pain, especially on one side

• Pain during intercourse (dyspareunia)

• A feeling of “heaviness” or dragging in the pelvis

• Irregular bleeding or spotting

• Referred pain to the lower back or legs

• Pain made worse by certain movements or positions

These symptoms can persist even after surgery for endometriosis or fibroids, leaving women frustrated and wondering why their treatments didn’t work.

The Complication with Endometriosis

Endometriosis and Allen-Masters Syndrome can coexist—and when they do, they complicate each other.

Endometriosis and Allen-Masters Syndrome can coexist—and when they do, they complicate each other.

Here’s how:

1. Mimicking or Masking Each Other

AMS pain can feel nearly identical to endometriosis. In laparoscopic surgery, torn ligaments or peritoneal defects might be mistaken for endometriosis—or missed entirely.

2. Worsening Each Other

The uterine instability caused by AMS may increase friction and inflammation in the pelvis, potentially exacerbating endometriosis symptoms. Likewise, the invasive nature of endometriosis can weaken uterine ligaments, creating a cycle of worsening pain.

3. Delaying Diagnosis

Because AMS isn’t well known, many surgeons focus only on excising visible endometriosis lesions. If ligament tears or pelvic instability aren’t also addressed, pain may persist despite "successful" surgery.

4. Influencing Fertility

While endometriosis is a known contributor to infertility, AMS can add to the challenge by altering the position of the uterus, interfering with sperm transport, or making embryo implantation more difficult.

Diagnosis: Why It’s Often Missed

AMS is best diagnosed through clinical examination and often requires a high index of suspicion from an experienced gynecologic surgeon. Imaging like MRI or ultrasound may not show ligament damage clearly. In some cases, laparoscopic exploration is the only way to confirm it, by observing a hypermobile uterus or peritoneal defects (like dimples or windows in the pelvic lining).

Unfortunately, many OB/GYNs are not trained to look for Allen-Masters Syndrome, which means it’s often overlooked—especially in patients already diagnosed with endometriosis

What Can Be Done?

If AMS is suspected, the treatment may include:

• Pelvic physical therapy to support surrounding muscles and reduce pain

• Surgical repair or suspension of the damaged ligaments, often during laparoscopy

• Pain management strategies including nerve blocks or hormonal regulation if endometriosis is also present

• Lifestyle modifications to reduce strain on the pelvis (avoiding certain exercises, managing constipation, etc.)

The Takeaway

Allen-Masters Syndrome may not be as well-known as endometriosis, but its impact is very real—especially for women who feel like they've tried everything and still have no answers.

If you’ve had surgery for endometriosis and your pain persists, or if your symptoms don’t quite fit the typical endo profile, it might be worth asking your doctor about Allen-Masters Syndrome.

Women deserve full answers—not partial relief.

Sources & Further Reading

• Howard FM. (2003). Chronic Pelvic Pain. Obstetrics and Gynecology

• Vercellini P et al. (2006). Chronic pelvic pain: pathogenesis and therapy. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology

• Tu FF et al. (2017). Beyond Endometriosis: Recognizing and Treating Comorbid Pelvic Pain Disorders. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology

Join Us: Make a Difference Today

Your support can transform lives. Every donation helps us fund research, advocate for better care, and provide essential grants to women facing debilitating conditions.

Join Us: Make a Difference Today

Your support can transform lives. Every donation helps us fund research, advocate for better care, and provide essential grants to women facing debilitating conditions.

Follow the Money: We Can Do Better

I want to start by saying: this post is not political. This post is about our shared experiences as women—as a mother of three daughters, a grandmother, and a friend to countless women who have been frustrated and overwhelmed by the current state of our medical system.

We have a common experience—and it needs to be heard and shared.

I was encouraged to write this after reading that the Gates Foundation just pledged $2.5 billion toward women’s health initiatives. But reading the accompanying article published in STAT left me deeply frustrated. The statistics on women’s health haven’t improved enough.

“The Gates Foundation said the goal of the new initiative is to address a long-running deficit in medicine that has disfavored women’s health—to the extent that the ‘typical’ patient described to medical students has traditionally been male.”

— STAT News

In a BMJ article published last week, Ru Cheng, the foundation’s Director of Women’s Health Initiatives, shared that only 1% of global research and development funding is allocated to women’s health issues outside of oncology, and between 2013 and 2023, only 8.8% of NIH-funded research focused exclusively on women.

These are not opinions. These are widely reported, peer-reviewed statistics from respected medical journals. And this is why women with Endometriosis or Adenomyosis are subjected to 8-10 years of medical gaslighting before they are diagnosed. And this is why women with these diseases literally need to be cut open in order to diagnose their disease. It's just not acceptable that laparoscopic surgery is required for diagnosis in 2025. We should be much further along by now. Do you realize that most endometriosis lesions cannot be detected on scans or imaging? I know this can be figured out! Progress is being made, let's push it along.

Men’s and women’s health issues are not treated with the same urgency or investment. That’s not a radical feminist opinion or a political talking point—it’s a follow-the-dollars reality.

The gaslighting women experience around this issue doesn’t just come from doctors. I’ve had people close to me—both men and women—try to argue that women’s health isn’t being overlooked, that maybe we’re exaggerating. But the data is undeniable.

If our mothers, daughters, grandmothers, aunts, and female friends matter—if we believe them and value their lives—then it’s time to stop dismissing their pain. It’s time to pay attention to the statistics, follow the funding, and change our course.

That’s why we launched Our Daughters Foundation:

To fight for awareness, raise money for research, and provide visibility and hope.

When we first started on this path of setting up the foundation, I was shocked to learn that women weren’t even included in NIH-funded medical trials until 1993. That wasn’t so long ago. If you’re close to my age, that year probably feels recent (Jurassic Park was in theaters and Bill Clinton was president). Incredibly, only 1% of non-cancer healthcare R&D currently targets female-specific conditions.

The Gates initiative is a huge step—but it’s not enough.

Women are still underrepresented in studies involving pain management, cardiovascular disease, and autoimmune conditions—fields where female biology plays a huge role in how we experience disease and respond to treatment. Even more disturbing is the lack of research funding for diseases that exclusively affect women, like endometriosis, adenomyosis, PCOS, and uterine fibroids. These are not rare diseases and conditions, and for many women, they’re life-altering.

For Those Suffering Now...and Our Daughters in the Future

I hope you’ll join us in raising awareness about the women’s health conditions that affect the people we love—and the people you love. These women are not statistics. They’re not being “dramatic” or “too emotional.” They are Mom, Nana, Auntie, Daughter, Friend.

As always, I’ve included data and references for everything I’ve shared above. (Again—thank you, ChatGPT, for helping curate these.) Please see the resources and stats below, which paint a clear picture of the disparities we’re up against.

— There is so much more to say, & even more that we can DO! Please help us make some noise!

With gratitude,

Kara

A Quick History Review

Thanks to ChatGPT research, here’s a timeline that puts things in perspective:1977 – The FDA banned women of childbearing age from participating in early drug trials. The reason? Hormonal “complexity” and fear of pregnancy-related liability (like the thalidomide crisis). That meant chemotherapy, heart meds, pain relief—all tested mostly on men.

1986–1987: The NIH began encouraging researchers to include women in funded studies. This was first published in the NIH Guide for Grants and Contracts

1993 – The NIH Revitalization Act required federally funded trials to finally include women and analyze sex-based differences.

The Pain Gap

Women experience chronic pain more frequently than men, but they’re still less likely to be treated seriously. A 2020 study of over 200,000 patients found:

Women consistently face longer delays and lower diagnostic accuracy than men—even for the same symptoms.

Women are:

Less likely to receive pain medication in the ER

Made to wait an average of 16 minutes longer

More likely to be told their symptoms are “psychological”

Despite the fact that 70% of chronic pain patients are women, 80% of pain research is still done on male animals or male subjects.

Let that sink in.

Sources

Reuters – Gates Foundation’s $2.5B women’s health initiative

STAT News: Women’s health funding still ignored

FDA 1977 guidance

NIH Revitalization Act

Medidata: History of women in clinical trials

NIH: Endometriosis Funding Summary

SELF: The PCOS Medical Mystery

New Security Beat: VC funding comparison

Statista: Hair Loss Pharma Market

RAND + WHAM Study on Economic Return

NIH: Gender Bias in ER Pain Treatment

Scientific American: Sex Bias in Pain Research